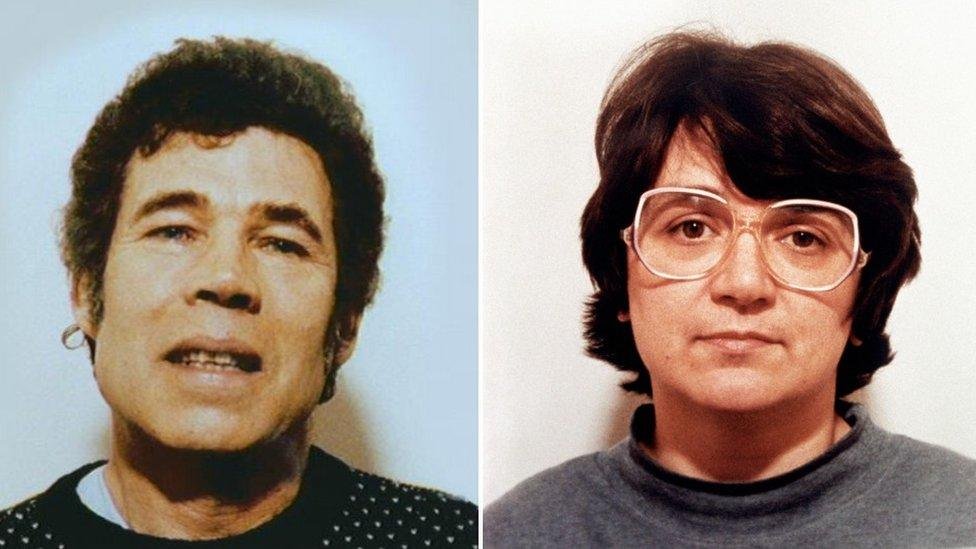

The crimes of Fred and Rose West remain among the most disturbing in modern British history. Over two decades, the couple murdered at least twelve women and girls, many of them within their own home at 25 Cromwell Street in Gloucester. Behind the façade of an ordinary terraced house lay a pattern of cruelty, sexual exploitation, and violence that would shock the nation when uncovered in the mid-1990s.

Yet the story of the Wests is not only about two killers. It is about the ways in which abuse can flourish behind closed doors, the failures of institutions to act on warning signs, and the vulnerability of those already living on the margins of society. The “House of Horrors” became infamous, but its real legacy lies in the questions it raised about safeguarding, social attitudes, and accountability.

Family Life and Abuse

Fred West’s background was marked by poverty, abuse, and violence. His early relationships were controlling and often violent, with signs of sexual deviancy apparent long before he met Rose. Rose West, born into a troubled home herself, was both a victim of early abuse and, in time, a perpetrator of it. By her mid-teens she was already displaying troubling behaviours, and when she met Fred in 1969, their relationship quickly evolved into a partnership defined by domination, cruelty, and sexual exploitation.

The West household soon became a site of abuse that was both hidden and normalised. They raised a large family, some children born to the couple and others from Fred’s previous relationships. The children were subjected to violence, humiliation, and sexual abuse. Discipline in the home was extreme, and testimony from survivors has since revealed the constant atmosphere of fear. The murder of Heather West, one of their daughters, demonstrated the extent to which family bonds were corrupted. Heather’s disappearance in 1987, later explained to siblings with the chilling threat that they could “end up under the patio like her,” highlighted how murder became woven into the family’s culture of control.

Rose West’s Prostitution

A central feature of the West household was Rose’s prostitution. Working from a bedroom in Cromwell Street, Rose took in clients while Fred played the role of facilitator and voyeur. At times, this extended beyond consensual sex work. Clients were sometimes violent, and there are accounts that Rose encouraged abuse within the household, blurring boundaries between her professional activities and the couple’s wider pattern of exploitation.

Rose’s work brought a stream of outsiders into Cromwell Street. For the children, this created an environment in which sexual activity, secrecy, and coercion were normalised. For victims, particularly vulnerable young women who boarded in the house or sought companionship there, it created opportunities for entrapment. This dual life, outwardly a domestic household, inwardly a site of prostitution and exploitation was central to how the Wests sustained their crimes.

The Victims

The victims of the Wests came from diverse backgrounds, but many were young women on the margins of society. Some were runaways, some were lodgers, and some were women the couple lured with offers of work or accommodation. Others were family members or stepchildren. What linked them was vulnerability and the Wests’ willingness to exploit it.

The cellar of 25 Cromwell Street was converted into a space of confinement, where women were abused and murdered. Victims were then buried in the cellar, beneath floorboards, or in the garden. The fact that these crimes could be committed in a terraced house in a busy neighbourhood underscores the ability of violence to remain hidden, even in plain sight.

Failures of Institutions

The exposure of the Wests’ crimes in the 1990s raised serious questions about how they had gone undetected for so long. Social workers had received reports of abuse in the household. Teachers had noted concerning signs in the West children. Neighbours sometimes reported disturbances. Yet intervention was minimal.

Part of this can be attributed to attitudes at the time. Domestic abuse was still widely regarded as a private matter, while allegations made by children were often dismissed as exaggeration. The stigma surrounding prostitution also played a role, as Rose’s sex work was treated as separate from wider concerns about the family’s behaviour.

The failure to protect the West children, and the victims who came into the household, is one of the enduring legacies of the case. It showed how institutional hesitation, combined with deep-seated social taboos, can leave the vulnerable without protection.

Arrest and Trial

By the early 1990s, rumours surrounding Heather West’s disappearance were intensifying. Teachers, social workers, and relatives had all questioned her whereabouts, but the family’s vague explanations that she had run away or gone to live elsewhere were never substantiated. For the other West children, Heather’s absence was a constant reminder of danger; Fred and Rose used her disappearance as a threat, warning them that if they misbehaved they would “end up under the patio like Heather.”

The catalyst came in 1992, when one of the West daughters confided in a friend at school about the sexual abuse she and her siblings suffered at home. This disclosure was passed on to police and social services, who began investigating the household. At first, the inquiry focused on child welfare, not murder, but suspicions about Heather’s fate soon grew stronger.

In February 1994, police obtained a search warrant for 25 Cromwell Street. Digging in the garden, they uncovered human remains that were soon identified as Heather’s. The scale of the crime scene widened dramatically as further excavations revealed additional bodies buried in the garden, under the cellar floor, and beneath the bathroom tiles. The house, outwardly a normal terraced home, became the most notorious crime scene in Britain.

Fred West was arrested and quickly charged with multiple murders. Initially, Rose was arrested only for offences related to child cruelty, but as police uncovered further evidence, including remains of women known to have visited the household, she too was charged with murder. The couple were kept in separate custody, and Fred attempted to shield Rose by claiming sole responsibility for the killings. However, police built a strong case linking her directly to several murders, including those of her stepdaughter Charmaine and her own daughter Heather.

As the case progressed, Fred’s behaviour became increasingly erratic. In January 1995, while on remand at HM Prison Birmingham, he took his own life by hanging in his cell. His suicide denied the courts the opportunity to test his full involvement and robbed the victims’ families of the chance to see him held accountable in public.

Rose West’s trial opened later that year at Winchester Crown Court. The decision to hold the proceedings outside Gloucester reflected both the scale of the case and the intense public interest. The trial, which lasted from October to November 1995, was one of the most heavily covered in British history, with international media descending on Winchester to report the details.

During the trial, the jury heard harrowing testimony from survivors, forensic experts, and investigators. The evidence was overwhelming: bodies had been buried at Cromwell Street and at Fred’s previous home in Much Marcle; Rose had played a central role in several killings; and she had actively participated in the control, torture, and abuse of victims. Testimonies from the West children painted a grim picture of life inside the household, describing a climate of constant fear and the normalisation of violence.

Rose West consistently denied involvement, portraying herself as a victim of Fred’s dominance. Her defence argued that Fred had manipulated her and carried out the murders without her consent. However, the weight of evidence contradicted this narrative. The jury was convinced not only of her knowledge but of her active participation in the killings.

On 22 November 1995, Rose West was found guilty of ten counts of murder. Mr Justice Mantell sentenced her to life imprisonment with a whole-life tariff, ensuring she would never be released. This sentence placed her among a very small group of women in Britain to receive such a punishment.

The conviction marked the end of one of the most complex and disturbing trials in modern British law. The demolition of 25 Cromwell Street the following year symbolised an attempt to erase the physical site of horror, though the memory of what occurred there continues to resonate in British public life.

Media, Memory, and Lessons

The exposure of the Wests’ crimes horrified the nation. The house on Cromwell Street became a focal point for grief and outrage, attracting crowds before it was eventually demolished to prevent it becoming a site of dark tourism. Media coverage was extensive, often sensationalised, but it also fuelled important debates about child protection, domestic abuse, and how easily violence can be hidden within seemingly ordinary families.

For Britain, the case remains a reminder that evil does not always operate in isolation. It can thrive in silence, in secrecy, and in institutions that fail to act. The Wests’ crimes were extreme, but the social dynamics that enabled them deference to family privacy, the marginalisation of certain victims, and the stigma around speaking out remain relevant.

An Editorial Reflection

Fred and Rose West’s crimes must be seen not only as a catalogue of murders but as a lesson in how abuse can embed itself within families, institutions, and communities. The brutality of the killings is undeniable, but the deeper tragedy lies in the missed opportunities to prevent them.

Editorially, the case compels us to ask hard questions. Why were children’s voices not believed? Why were reports of abuse not acted upon? Why did the façade of an ordinary family home prevent deeper scrutiny? These questions remain relevant today in safeguarding debates and in efforts to address domestic and sexual violence.

The West case is not just about two killers. It is about the silence that surrounded them, the institutions that failed to intervene, and the vulnerability of those who paid the price. Its legacy is a warning: that safety requires vigilance, accountability, and the courage to confront abuse, even when it hides behind the façade of normality.