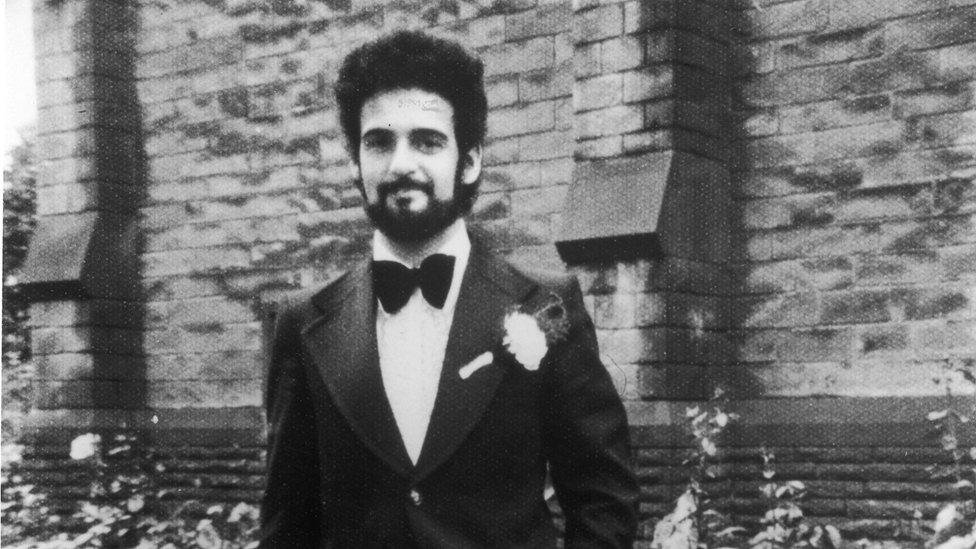

Few criminal cases have scarred the British psyche as deeply as that of the Yorkshire Ripper. The name itself became shorthand for fear, institutional failure, and a climate of misogyny that enabled a serial killer to evade capture for years. Between 1975 and 1980, Peter Sutcliffe, a lorry driver from Bradford, murdered thirteen women and attempted to kill at least seven more. His crimes not only terrorised communities across the North of England but also revealed profound flaws in policing, justice, and social attitudes.

As an editorial subject, the Yorkshire Ripper case transcends its criminal details. It forces a confrontation with questions about how women were perceived, how authorities responded, and how prejudice and incompetence allowed violence to thrive. To revisit the case is not merely to recount horrific murders; it is to explore the systemic conditions that permitted them, and to consider whether Britain has truly learned from one of its darkest episodes.

The Crimes and the Climate of Fear

Peter Sutcliffe’s first known murder was in October 1975, when he killed Wilma McCann in Leeds. She was struck with a hammer and stabbed multiple times. Over the following years, Sutcliffe’s attacks followed a chilling pattern: late-night assaults on women, often in secluded or poorly lit areas, using hammers, screwdrivers, and knives.

By 1977, the scale of his violence had become apparent, with multiple murders linked across West Yorkshire and Greater Manchester. Women altered their daily lives, fearful of venturing out alone at night. Parents warned daughters not to go out after dark, pubs reported falling attendance from women, and workplaces imposed curfews on female staff. The North lived under siege, not from terrorism or political unrest, but from one man exploiting indifference and incompetence.

The victims were not a homogeneous group. While several were sex workers, many were not. The suggestion that Sutcliffe specifically targeted prostitutes framed the case in a way that dehumanised victims and allowed authorities to rank their suffering. When university student Jacqueline Hill was murdered in 1980, the public outrage was notably sharper than in earlier cases. This distinction, between so-called “innocent” and “non-innocent” women, underpinned much of the flawed policing response.

Policing Failures and the Wearside Hoax

The police investigation into the Yorkshire Ripper is one of the most criticised in British history. West Yorkshire Police interviewed Sutcliffe nine times during the inquiry, each time releasing him without suspicion. Officers were diverted by a cruel hoax: a series of letters and an audio tape sent to detectives in 1978, signed “Jack the Ripper.” The recording, with a distinct Wearside accent, taunted police and claimed responsibility for the murders.

The hoax, later revealed to be the work of John Humble, known as “Wearside Jack,” fatally distracted investigators. Police devoted thousands of hours and resources to hunting a suspect with the wrong accent, while dismissing witnesses who described attackers sounding local. Sutcliffe, despite fitting key profiles and having been reported by acquaintances, was allowed to continue his killing spree.

The obsession with the tape also reflected a policing culture vulnerable to sensationalism and tunnel vision. Senior officers, desperate for a breakthrough, placed undue weight on a single piece of evidence while ignoring broader investigative failures. This myopia contributed directly to the deaths of additional women.

Misogyny and the Value of Women’s Lives

Perhaps more damaging than operational errors was the language and attitude displayed by authorities. The police frequently described victims as “innocent women” if they were not sex workers, and “not innocent” if they were. Such language reinforced public perceptions that some lives were worth more than others. The implication was that violence against sex workers was somehow less shocking or less deserving of urgency.

This institutional misogyny shaped the pace and focus of the investigation. It also had consequences for public trust: women in working-class communities, especially those engaged in sex work, were effectively told that their safety was of lower priority. The Yorkshire Ripper case thus became not just a story of one killer, but a mirror reflecting Britain’s ingrained prejudices against women, class, and marginalised communities.

Media Coverage and Sensationalism

The media’s role in shaping the public narrative cannot be ignored. Newspapers often echoed the language of police, distinguishing between “respectable” victims and those deemed less deserving of sympathy. Sensationalist headlines invoked comparisons with Jack the Ripper, reinforcing the idea that this was a story about infamy rather than a tragedy about real women.

At the same time, press coverage helped fuel public fear. Reports of curfews, police warnings, and sensationalised crime scene details created a climate in which women were advised to limit their movements rather than society demanding stronger action against the perpetrator. The press held power to shape opinion, but too often it chose to repeat damaging stereotypes rather than challenge them.

Impact on Feminist Movements

The Yorkshire Ripper murders coincided with the rise of feminist movements in Britain, particularly those addressing violence against women. For many activists, the case became a rallying point. Campaigners argued that the state’s failure to protect women and the demeaning language used by police reflected wider structural oppression.

Marches and protests challenged not only Sutcliffe’s violence but also the systemic attitudes that allowed it to continue. Slogans such as “No Curfews for Women, Curfew for Men” captured the anger that women were being asked to modify their behaviour while men’s violence went unchecked. In this sense, the Yorkshire Ripper case did not just expose misogyny; it energised movements determined to confront it.

Arrest, Trial, and Prison Life

Sutcliffe’s capture in January 1981 was almost accidental. Arrested in Sheffield for driving with false number plates, he was found to be carrying weapons. When questioned, he confessed to the murders, though he claimed to be following divine instructions. This defence was ultimately rejected, and he was convicted of thirteen murders and seven attempted murders. He received twenty concurrent life sentences, later converted to a whole life order.

In prison, Sutcliffe remained a figure of morbid fascination. He was attacked by fellow inmates multiple times, once being blinded in one eye. He spent much of his sentence in Broadmoor Hospital under psychiatric care before being returned to prison. He died in November 2020 from complications related to COVID-19, closing a chapter but not ending the debates surrounding his crimes.

Comparisons with Other Investigations

The Yorkshire Ripper case has often been compared with other major serial killer investigations, including those of Harold Shipman and Fred and Rose West. In each, questions arose about missed opportunities, flawed assumptions, and the weight of institutional bias. But Sutcliffe’s crimes stand apart for their sheer impact on everyday life in the North of England, creating an atmosphere of terror akin to wartime restrictions.

Unlike later cases, the Ripper inquiry also highlighted how hoaxes and sensationalist distractions can derail an investigation. The Wearside Jack episode remains one of the most notorious examples of how easily policing priorities can be misdirected by single pieces of misleading evidence.

Lessons and Legacy

The Yorkshire Ripper case left Britain with lessons that remain relevant. It exposed the danger of prejudiced policing, the perils of tunnel vision in investigations, and the devastating impact of societal attitudes towards women. It also revealed how communities can be paralysed by fear when authorities fail to protect them.

The inquiry into the failures, led by Sir Lawrence Byford in 1981, concluded that the police had committed fundamental errors and missed opportunities. The report, long suppressed, acknowledged the scale of incompetence but also underscored the need for structural reform in British policing.

The case remains a touchstone in discussions about violence against women. Campaigners argue that while society has progressed, echoes of the same prejudices persist: women’s safety is still too often compromised, reports of sexual violence remain under-investigated, and stereotypes continue to influence justice.

An Editorial Reflection

Editorially, the Yorkshire Ripper case must be seen not only as a grim series of crimes but as a collective failure. Sutcliffe’s murders were horrific, but the enduring shame lies in how preventable some of them may have been. The women he killed were not collateral damage in a manhunt; they were individuals failed by systems that dismissed them.

The police were under-resourced and misled, but they were also blinkered by their own biases. The media, too, amplified distinctions between “respectable” and “non-respectable” victims, shaping public opinion in ways that diminished empathy for certain women. The public narrative became as much about who “deserved” sympathy as it was about stopping a murderer.

For Britain today, remembering the Yorkshire Ripper case is about more than recalling a serial killer. It is about acknowledging how institutions once reflected and, in some ways, still reflect societal prejudices. If progress is to be measured, it must be in the willingness to confront uncomfortable truths: that violence against women is systemic, that class and occupation still affect justice, and that real safety requires more than warnings to stay indoors.